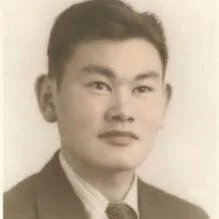

Fred T. Korematsu

Fred T. Korematsu was a national civil rights hero. In 1942, at the age of 23, he refused to go to the government’s incarceration camps for Japanese Americans. After he was arrested and convicted of defying the government’s order, he appealed his case all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled against him, arguing that the incarceration was justified due to military necessity.

Photo by Lia Chang

Photo by Shirley Nakao

In 1983, Prof. Peter Irons, a legal historian, together with researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, discovered key documents that government intelligence agencies had hidden from the Supreme Court in 1944. The documents consistently showed that Japanese Americans had committed no acts of treason to justify mass incarceration. With this new evidence, a pro bono legal team re-opened Korematsu’s 40-year-old case on the basis of government misconduct. On November 10, 1983, Korematsu’s conviction was overturned in a federal court in San Francisco. It was a pivotal moment in civil rights history.

Korematsu remained an activist throughout his life. In 1998, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, from President Bill Clinton. In 2010, the state of California passed the Fred Korematsu Day bill, making January 30 the first day in the U.S. named after an Asian American. Korematsu’s growing legacy continues to inspire people of all backgrounds and demonstrates the importance of speaking up to fight injustice.

Early Life

Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919. He was the third of four sons to Japanese immigrant parents who ran a floral nursery business in Oakland, California.

After the U.S. entered World War II, Korematsu tried to enlist in the U.S. National Guard and U.S. Coast Guard, but was turned away by military officers who discriminated against him due to his Japanese ancestry. Korematsu then trained to become a welder, eventually working at the docks in Oakland as a shipyard welder and quickly rising through the ranks to foreman. One day, when he arrived to punch in his time card, Korematsu found a notice to report to the union office, where he was suddenly fired from his job due to his Japanese ancestry.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii by Japan on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the U.S. military to remove over 120,000 people of Japanese descent, the majority of whom were American citizens, from their homes and forced them into American prison camps throughout the United States.

Photo courtesy of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute

Arrest and U.S. Supreme Court Case

Fred Korematsu chose to defy the order and carry on his life as an American citizen. He underwent minor plastic surgery to alter his eyes in an attempt to look less Japanese. He also changed his name to Clyde Sarah and claimed to be of Spanish and Hawaiian descent. On May 30, 1942, he was arrested on a street corner in San Leandro, California, and taken to San Francisco county jail. While in jail, he was visited by Ernest Besig, the director of the San Francisco office of the American Civil Liberties Union, who asked Korematsu if he was willing to become the test case to challenge the constitutionality of the government’s imprisonment of Japanese Americans. On September 8, 1942, Korematsu was convicted in federal court for violating the military orders issued under Executive Order 9066. He was placed on a five-year probation. For several months, he lived at the Tanforan “Assembly Center” in San Bruno, CA, one of the former horseracing tracks where Japanese Americans were first held before being sent to the more permanent American concentration camps. Korematsu and his family were transferred from Tanforan to Topaz, Utah, where the government had set up one of 10 incarceration camps for Japanese Americans.

Topaz Incarceration Camp in Topaz, Utah

Photo courtesy of Utah.gov

Believing the discriminatory conviction went against freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, Korematsu appealed his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In its December 1944 landmark decision, the high court ruled against him in a 6 to 3 decision, declaring that the incarceration was not caused by racism, and was justified by the Army’s claims that Japanese Americans were radio-signaling enemy ships from shore and were prone to disloyalty. The court called the incarceration a “military necessity.” In one of the three stinging dissents, Justice Robert Jackson complained about the lack of any evidence to justify the incarceration, writing: “the Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination … The principle then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Following World War II and the release of Japanese Americans from the concentration camps, Korematsu attempted to resume life as an American citizen. He moved to Detroit, Michigan where his youngest brother resided. There, he met his soon-to-be wife, Kathryn, a student at Wayne State University who was originally from South Carolina. At the time, anti-miscegenation laws prohibited interracial marriage in states including California and South Carolina, but mixed-race marriage was legal in Michigan. Fred and Kathryn Korematsu married in Detroit before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1949, where they raised two children, Karen and Ken.

Re-opening of Korematsu's U.S. Supreme Court Case

Korematsu maintained his innocence through the years, but his U.S. Supreme Court conviction had a lasting impact on his basic rights, affecting his ability to obtain employment.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed a special commission to instigate a federal review of the facts and circumstances around the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In June 1983, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) concluded that the decisions to remove those people of Japanese ancestry to U.S. prison camps occurred because of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

During this time, University of California San Diego political science professor Peter Irons, together with researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, stumbled upon secret Justice Department documents while researching government archives. Among the documents were memos written in 1943 and 1944 by Edward Ennis, the U.S. Justice Department attorney responsible for supervising the drafting of the government’s brief. As Ennis began searching for evidence to support the Army’s claim that the incarceration was of military necessity and justified, he found precisely the opposite — that J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI, the FCC, the Office of Naval Intelligence and other authoritative intelligence agencies categorically denied that Japanese Americans had committed any wrongdoing. These official reports were never presented to the U.S. Supreme Court, having been intentionally suppressed and, in one case, destroyed by setting the report afire.

It was on this basis — governmental misconduct — that a legal team of pro-bono (voluntary and free-of-charge) attorneys successfully reopened Korematsu’s case in 1983, resulting in the overturning of his criminal conviction for defying the incarceration. During the litigation, U.S. Justice Department lawyers offered a pardon to Korematsu if he would agree to drop his lawsuit. In rejecting the offer, Kathryn Korematsu remarked, “Fred was not interested in a pardon from the government; instead, he always felt that it was the government who should seek a pardon from him and from Japanese Americans for the wrong that was committed.”

On November 10, 1983, Judge Marilyn Hall Patel of the U.S. District Court of Northern California in San Francisco formally overturned Korematsu’s conviction. It was a pivotal moment in U.S. civil rights history. Mr. Korematsu stood in front of Judge Patel and stated, “According to the Supreme Court decision regarding my case, being an American citizen was not enough. They say you have to look like one, otherwise they say you can’t tell a difference between a loyal and a disloyal American. I thought that this decision was wrong and I still feel that way. As long as my record stands in federal court, any American citizen can be held in prison or concentration camps without a trial or a hearing. That is if they look like the enemy of our country. Therefore, I would like to see the government admit that they were wrong and do something about it so this will never happen again to any American citizen of any race, creed or color. ” Although Judge Patel’s ruling cleared Korematsu’s conviction, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1944 ruling still stands. It would require a similar test case, involving a mass banishment of a single ethnic group, to challenge the original Supreme Court decision.

Read Judge Patel’s full decision granting Korematsu’s petition for writ of coram nobis. 584 F.Supp. 1406 (N.D. Cal. 1984)

Japanese American Redress Movement and Post-9/11 Activism

Korematsu remained an activist throughout his life. After his conviction was overturned, Korematsu became an active member of the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations. He traveled to Washington DC and helped lobby for the passage of the bill which would grant an official apology from the U.S. government and a token compensation of $20,000 for each surviving Japanese American that was incarcerated. Although President Ronald Reagan had initially opposed the redress and reparations legislation, he soon reversed his position due to political pressure and an increasing effort on behalf of Japanese Americans to seek economic, legal and political redress. On August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed the redress and reparations legislation into law.

In 1998, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, from President Bill Clinton. He was invited to speak at numerous events and university campuses all over the United States about his experience, including the University of California at Berkeley, Stanford University, Georgetown University, University of Michigan, Harvard and Yale.

After 9/11, Korematsu continued to speak out. In 2003, he filed a “Friend of the Court” amicus brief with the U.S. Supreme Court for two cases appealed before the Supreme Court of the United States, on behalf of Muslim inmates being held at Guantanamo Bay: Shafiq Rasul, v. George W. Bush and Khaled A.F. Al Odah v. United States of America. In the brief, he warned that the government’s extreme national security measures were reminiscent of the past. In 2004, he filed a similar brief on behalf of an American Muslim man being held in solitary confinement in a U.S. military prison without a trial.

Similarly, in his second amicus brief, written in April 2004 with the Bar Association of San Francisco, the Asian Law Caucus in San Francisco, the Asian American Bar Association of the Greater Bay Area, Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, and the Japanese American Citizens League, Korematsu responded to Donald Rumsfeld v. Jose Padilla. The amicus brief’s statement of interest emphasized the similarity of the unlawful detainment of Fred Korematsu during WWII and that of Jose Padilla following the events of 9/11 and warned the American government of repeating their mistakes of the past. He believed that “full vindication for the Japanese Americans will arrive only when we learn that, even in times of crisis; we must guard against prejudice and keep uppermost our commitment to law and justice.”

Passing and Growing Legacy

On March 30, 2005, Mr. Korematsu died of respiratory failure at the age of 86. Hundreds of people packed his memorial service at First Presbyterian Church in Oakland, CA to pay their final respects to a civil rights icon. He is survived by his wife, Kathryn, daughter, Karen, and son, Ken.

In 2010, the state of California passed the Fred Korematsu Day bill, making January 30 the first day in the US named after an Asian American. Korematsu’s growing legacy continues to inspire people of all backgrounds and demonstrates the importance of speaking up to fight injustice.

Learn more on the Fred T. Korematsu Institute website, KorematsuInstitute.org.